May 21st, 1930. My father, nineteen years old is released from prison and deported to Canada where he was born. He had served three years in the US Washington state prison for adults after stealing a government cheque for $65. As a convicted criminal he was banned for life from returning to his homeland in Oregon leaving behind his parents, grandparents, three brothers, four sisters, aunts, uncles and cousins. Unemployment in Canada was thirty percent following the collapse of international trade and the dust bowl catastrophes of the prairies. Transients were taking to the roads and rails, hopping freight cars, establishing hobo jungles on the outskirts of cities and towns across the country.

A year after his deportation, my father married an English lass. But after learning her new husband had been in prison, she boarded a ship for England, pregnant with their child. Five years later, with a new identity my father met and married my mother telling her he was alone and had no family.

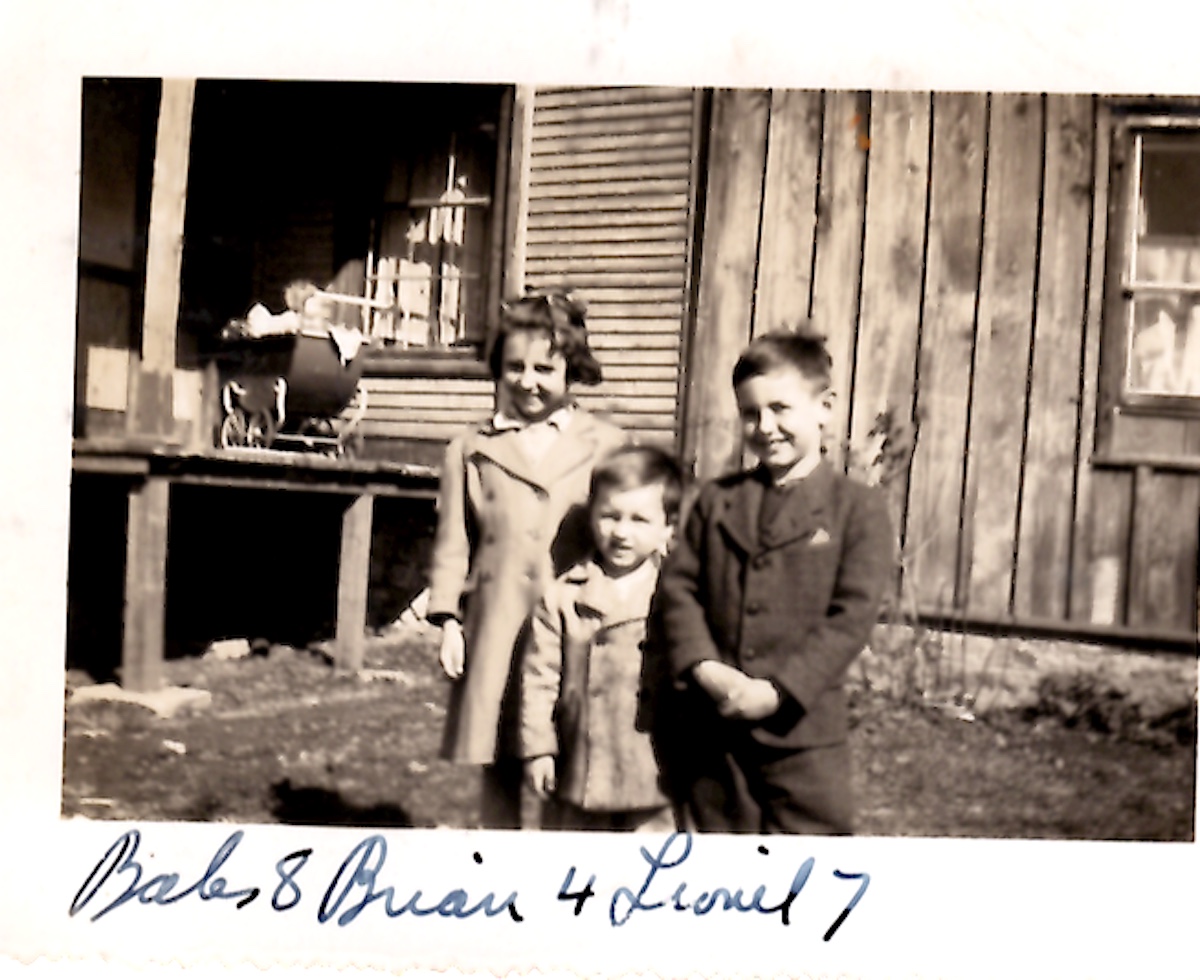

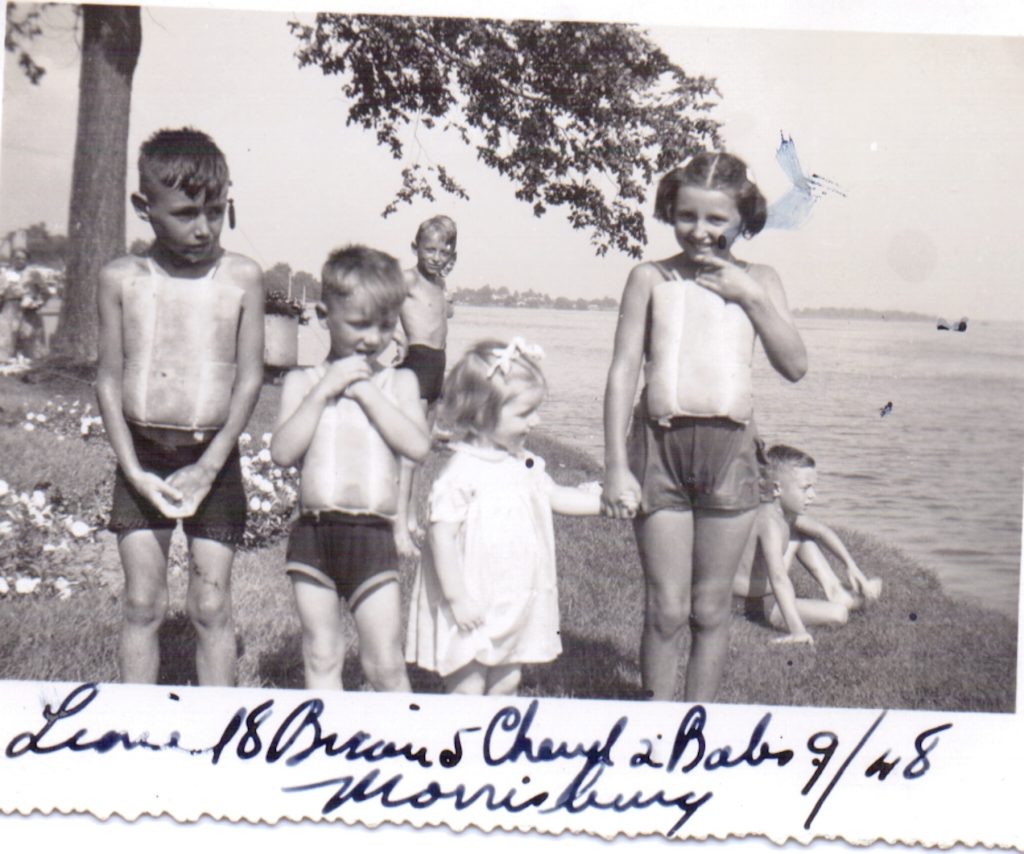

Like many families during that time my parents struggled to get by with little government support, moving often, searching for work. Each of my three siblings were born in different places; my sister in Montreal, my older brother in Toronto, the younger one on a farm in rural Ontario. In the summer of 1944 my father moved the family again, this time to a rooming house in the small village of Morrisburg, an hour’s drive from Ottawa. My mother did not know at the time, she was pregnant with me.

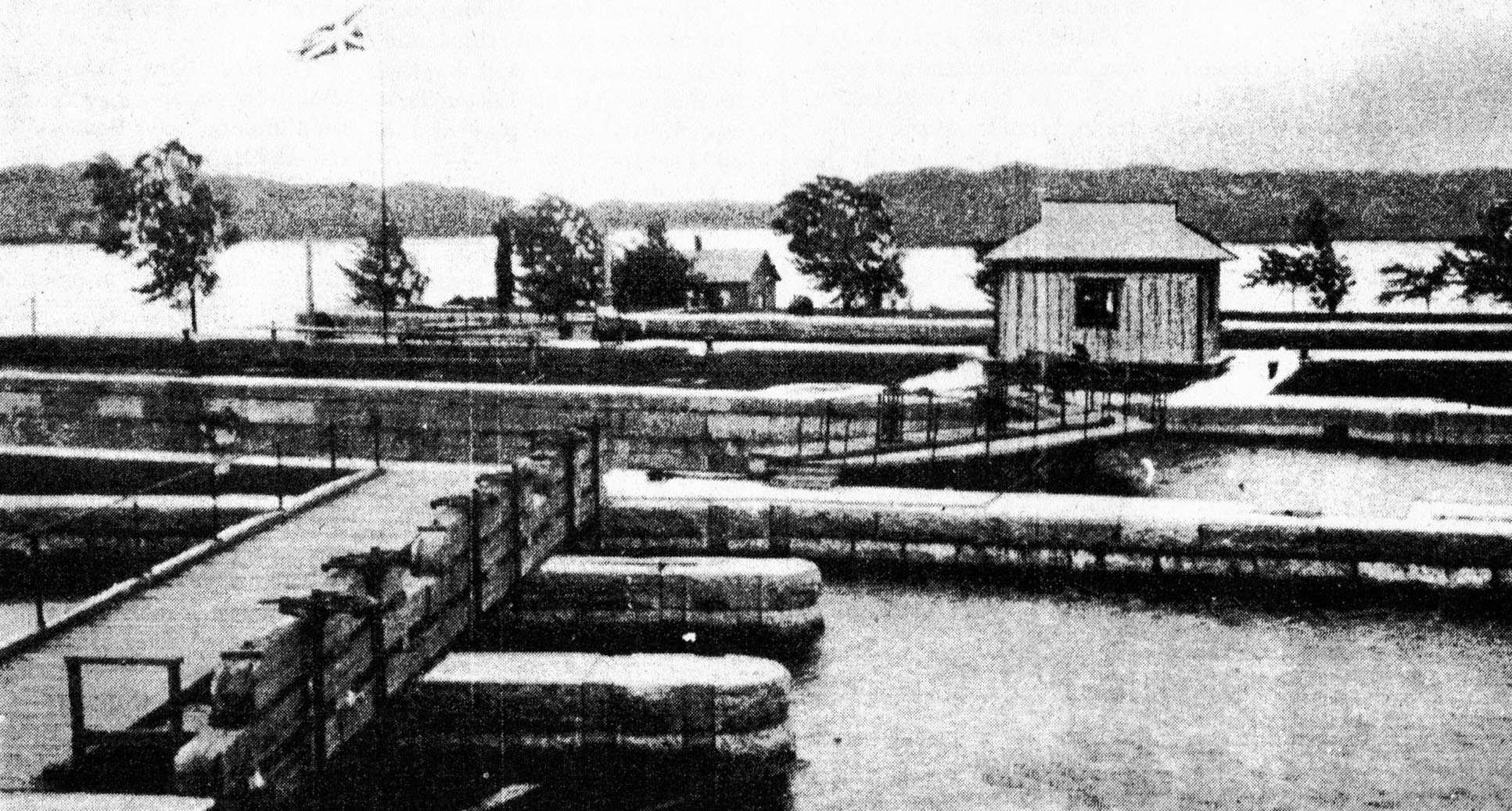

As the economy slowly stumbled to recovery and headlines announced triumph and battle wins over Nazi Germany, the mood of the country changed. In every living room, radios blasted out soaps and sitcoms featuring loving wives, friendly neighbors and prosperity for all. The good times we’re here to stay. Government discussions focussed on what was owed to the tens of thousands of Canadian women and men in uniform coming home. Added to the general excitement across the country was the local buzz about the building of the St Lawrence Seaway with Morrisburg at the heart of it. Though most of the town would be flooded, there would be jobs, compensation for new housing, a new Main Street and the possibility of a heritage village. People would be flocking from all corners of the earth to visit the site of the great engineering fete of the century. The Queen of England it was said, might attend the opening. Shopkeepers, school teachers, garbage collectors; everyone joined in the fever of speculation. Even telephone operators recognizing voices while connecting calls, couldn’t resist adding their own two cents worth. Hopes and dreams, dormant for years during the Great Depression followed by six years of war, surfaced. My father could not have wished for a better place to prosper.

Connecting with people was as natural to my father as breathing, his gentle demeanor, soothing voice and magnetic charm instantly gaining the trust of complete strangers. In a matter of months he had the ear and confidence of the Morrisburg town council and business elite, convincing them to invest in his ideas and dreams for the town. Given the optimism prevalent at the time of his arrival and his winning personality, success should have been his; alas it was not.

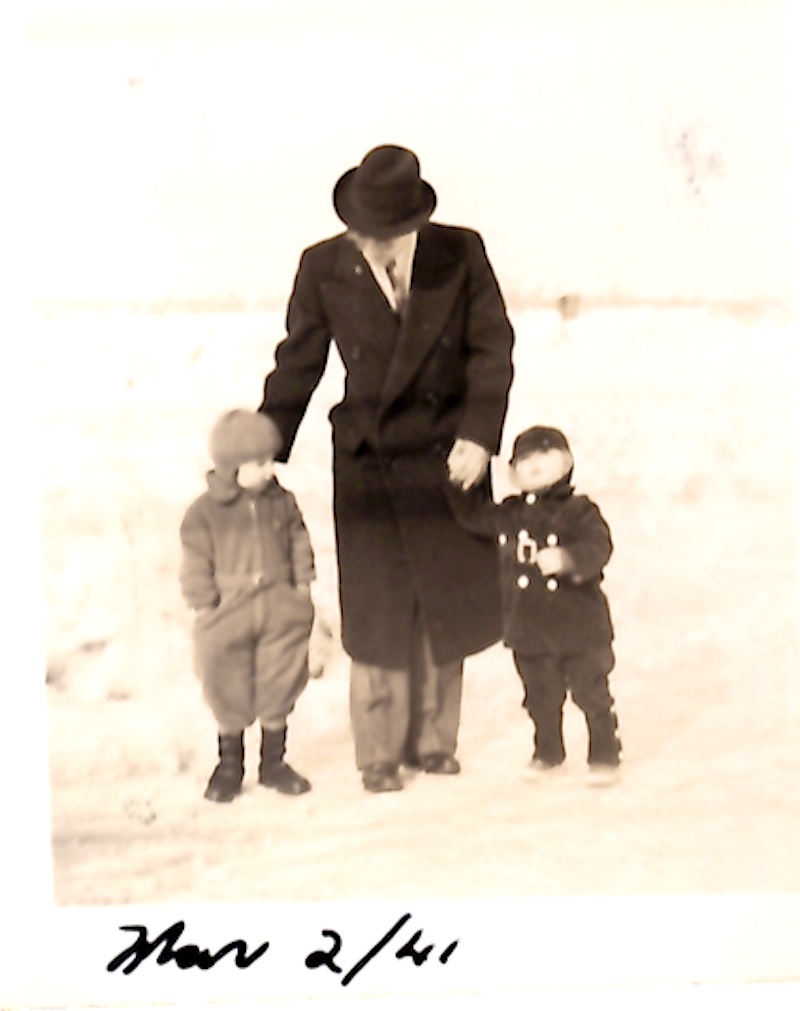

I was three months old the morning my father got up as usual, put on the shirt my mother had washed and pressed and donned his immaculate suit before setting out for his job as a traveling salesman. He took longer than usual to say goodbye to us, my mother recalled later; joking with my siblings, lingering over kisses, even picking me up from my pram and hugging me before touching his fedora hat in a farewell gesture and disappearing through the back door. We never saw or heard from him again. Years later I would listen to our neighbors, the Steinburgs, speak of him with fondness in their voices. “ This was your father’s business,” they told me as I helped grade eggs in their garage, placing each one on a conveyor belt where they were dropped into boxes according to weight. “He had some good ideas,” they would add shaking their heads, the memory of him no more than a fleeting moment drifting across their minds. Looking back I wonder how we all survived. My mother was a stranger in town. She had no friends or relatives, no money and a husband who had skipped town leaving behind a trail of debts and broken promises. Clare Beckham, the local policeman ruled the town. He was convinced my mother was part of my father’s dreams and schemes. He could not have been more wrong.

We lived in two rooms on the ground floor at the back of a two story house right across from the canal. The back door opened to the outside. Inside another door led to a staircase to the upper floor where all the rooms were occupied. As an adult I shudder at the thought of a small child having to pass a drunken man sprawled on the stairs trying to grab her legs as she headed for the only bathroom. But as that child I was more annoyed than threatened; to me he was no more than an irritating bundle to get past. I was in charge. More than seventy years later I still marvel at the unspoken lessons my mother instilled in me; this mild mannered, single minded woman with a determination of steel. One day in particular, just an ordinary day, is embedded in my mind, every detail crystal clear.

I am three years old, sitting at a large table. My siblings have all left for school. It is hot. A blind is drawn over the only window to keep out the sun, so the room is dark. My mother’s back is to me. She is leaning over a washboard set in a tub of water on a chair, one hand moving the clothes up and down the board, the other holding a bar of yellow soap she dips in and out of the tub. She says nothing, occasionally wiping her brow with the back of her hand. In front of me is a bowl of cold porridge. All other breakfast dishes have been cleared away and the table is set for lunch. She had told me once and only once, to eat my porridge; either for breakfast, lunch or supper. I watch the hands of the clock on the wall slowly move. When both are pointed up, I am free; to race out the door, run to the curb a few steps away and watch for my big brother Lionel coming home from school. I knew for certain that if I stepped one foot off the curb, that privilege would end and I would never again know the thrill of my big brother rushing toward me, sweeping me up on his shoulders, twirling me around laughing, showing me off to his friends. Once inside, I look across the room at my mother and see her face lit up in delight watching us. She was not angry about the porridge. She had given me a choice and I was in charge.

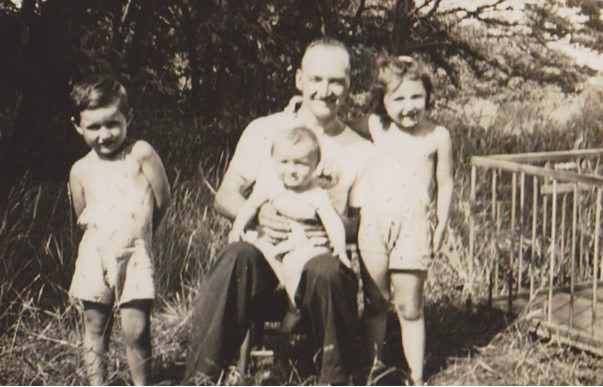

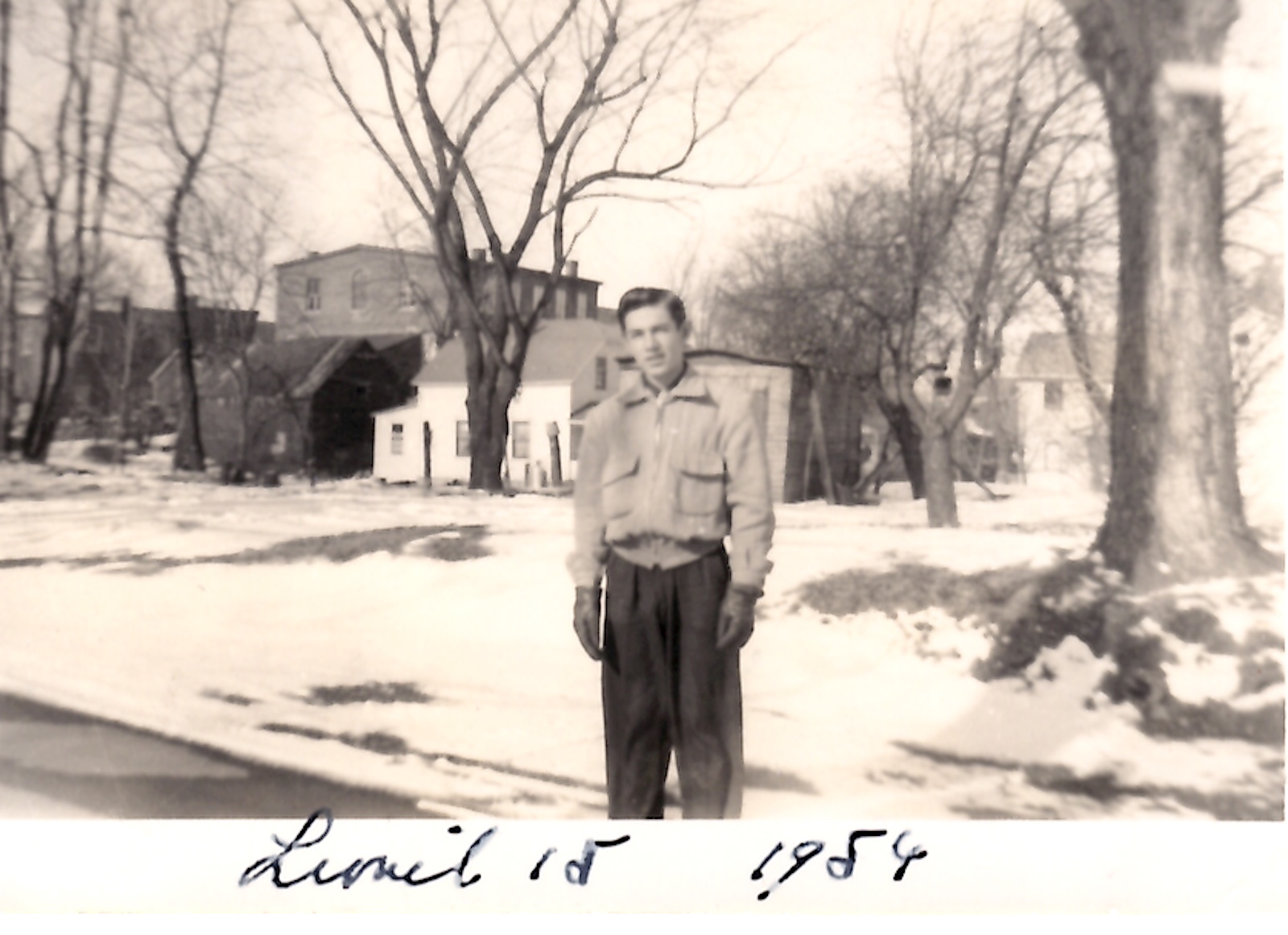

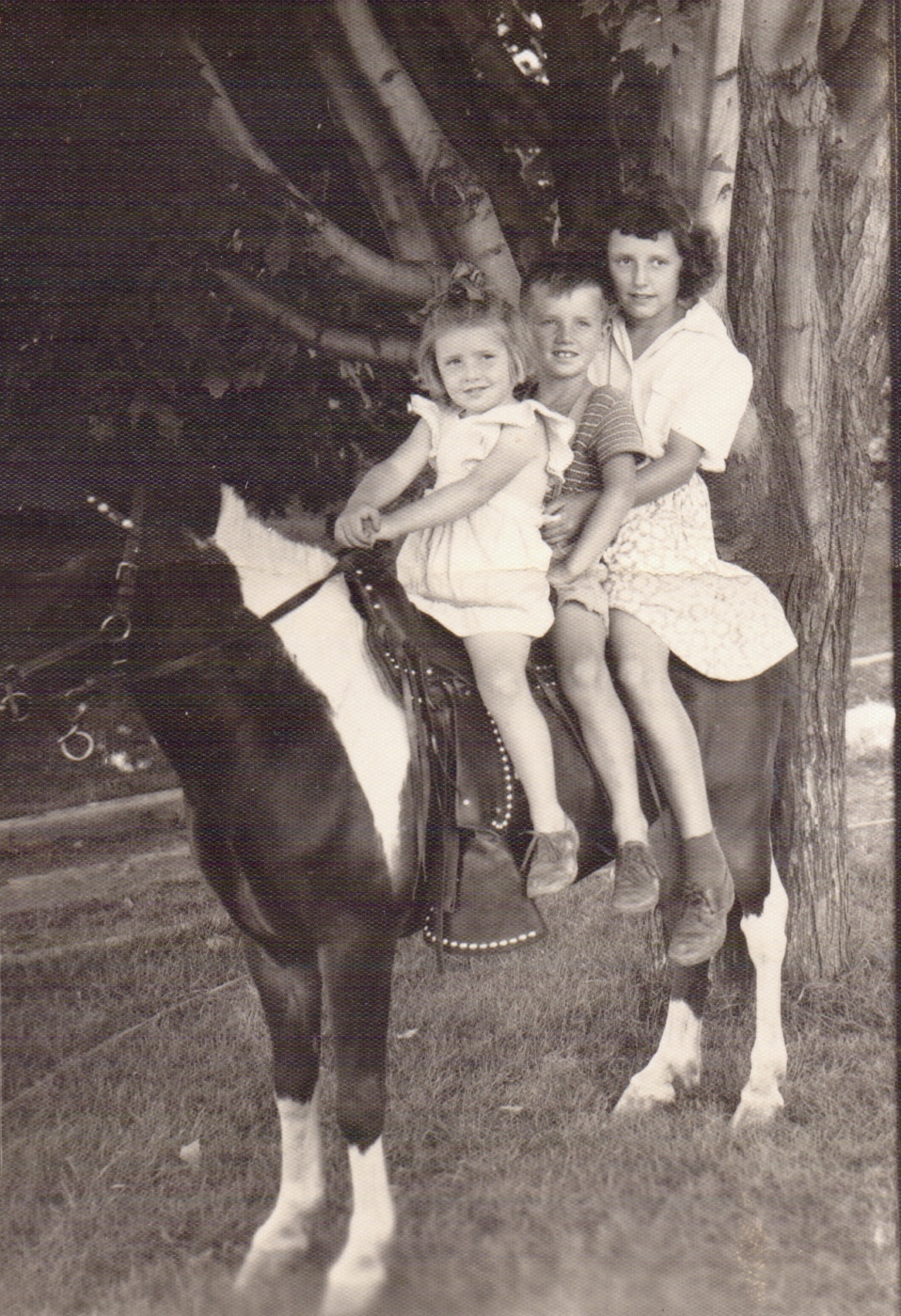

During summer months my brother Brian and I watched from the window of Miss Moor who lived upstairs, as each boat loaded with wheat and other goods, passed through the locks into the canal making their way to an ocean a thousand miles away and on to Europe. But here the canal was our playground, swimming in it during summer and skating on it in winter. On warm Sundays my mother walked us all across a series of concrete footpaths over the locks to a park by the river where we could play and swim. Leaning over a Kodak Brownie box camera, her hand on top shielding the sun, she would call, “Look at the birdies,” and smile. Film was expensive, development even more but she took photos of us all as we grew, writing in the white margins of each, our names, ages and dates.

Over time, folks came to recognize my mother as the honest, straightforward person she was. But not everyone wanted their children mixing with the Bells. My best friend, Mary Lynn Racher would sneak me into the back yard of her house to play on her swing. But when her mother heard us, she would appear on their veranda, order Mary Lynn inside and tell me to go home. Both characters turn up as Lisa and Mrs. Finnegan in my novel, ‘When the Magpie Calls.’

After five years in two rooms we moved to a real house in a block of five a few streets in from the canal. Finally we had a back yard, a shed where we kept chickens, an upstairs all our own and an eat-in kitchen. My mother’s prize possession was the washing machine she saved up to buy. “Always use cash,” she would say.” Your father bought everything on time and soon collectors turned up at the door to take back the items; furniture, and once a fur coat he bought for me. He liked nice things but couldn’t afford them.”

The washing machine was white, round, stood on legs and had a heater and motorized rollers. I was allowed to catch the sheets from the back as they were fed through the rollers, but never in front for fear of trapping my fingers. On the wood stove a large pot of clear thick liquid bubbled, the clean smell of home-made starch filling the room; in it she dipped collars, cuffs and pillowcases before hanging it all on clothes lines outside. In winter, freezing sheets would sway stiff like boards next to shirts lined up like white scarecrows. When dry she would iron it all, folding shirts as if new from the store. Wrapping each pile of laundry in brown paper, she tied them up with string, labeled and stacked each parcel on a wooden wagon with a long handle ready for delivery. In winter months she replaced the wheels with sled skis. When I was seven, I was allowed with my brother Brian to deliver the packages all over the village earning our weekly pocket money of 25 cents; enough for the Saturday movie and popcorn at the Cameo theatre, a saltbox building next to the beauty parlor on Main Street. My sister, fourteen, worked as a waitress to buy her clothes and Lionel bought a bike with his paper route money.

A family of six Irish redheads lived at one end of the block; the dad had fiery red hair, was full of fun and always in conflict with either neighbors or the police. The Aemons, a very proper English family lived at the other end of the block and gave us clothes their two children had outgrown. Our next door neighbors, the Hess family owned a grocery store where my mother was obliged to shop with her government food stamps. They also owned the newest invention, a television. From their living room couch my brothers and I watched ‘I Love Lucy’ shows, guessing more than seeing their images behind the snowy screen. The Lopers, a deaf mute couple made up the rest of the block. Their son was the same age as my brother Brian and could hear and speak like the rest of us, using sign language to argue with his parents. Ruth, their daughter went to college in Ottawa; a fact that took up residence in my mind like a whispering wind- one day maybe.

During hot summer months, my mother hung out with neighbors on the wooden platforms in front of each door watching kids play ball games, skip and ride bikes in the front yard. She was friendly with our neighbors but they never came into our house. The activity she reserved for herself was her love of painting. Knowing how intensely involved one is while painting a subject, I am in awe at the watercolor painting she did of my father, years after he had deserted us.

Friday night was bath night in a tin tub in the kitchen, filled with hot water heated on the wood stove that served to warm the house by way of ceiling vents. Being the youngest I was first to bathe and first to bed. Crouching with my ear to the ceiling vents while the others bathed, I was privy to all that was happening in our household; the troubles my brother Brian was in when Clare Bickham came knocking at the door, the details of my sister’s arguments with my mother about clothes and boys, and letters she read aloud from my grandmother thousands of miles away in England, begging her to leave Morrisburg. I had met my grandmother when I was three; her visit prompted by my mother informing her of my father’s desertion three years earlier. Moving near her was exciting to me. I loved the parcels she sent. Best of all, my Aunt Phyllis would teach me to play the piano. Mum was so proud of her sister. “When Phyllis played,” she would say, shaking her head, “she was completely absorbed in a world all her own. She had a brilliant career as a concert pianist ahead of her. Then her voice would become quiet, she would turn her head away. There was something very strange about Phyllis.

There were few books, toys or music in our home, and certainly no money for lessons or outings; instead mother used privileges to inspire and discipline us. Extra chores got us five more minutes before bed; failure to do assigned tasks or arrive home late sent us to bed early. She made cakes, had parties for our birthdays and played cards and games with us. At Christmas my brothers fetched the largest tree they could muster from the woods, set it up in our living room ready for decoration by all of us. On Christmas morning we rushed to our stockings filled with oranges, sweets, new socks and underwear. Once a year we boarded a bus to the small village of Iroquios for our annual dental checkup followed by ice cream. For a singing contest when I was five she wrapped my hair in rags to make Shirley Temple ringlets, starched and pressed a second hand dress of soft rainbow colors and was beaming with pride when I won.

For ten years my mother had made her living by washing the clothes and linens of the town’s elite. Finally she gave in to my grandmother and plans were made to uproot and move to England. All the neighbors and half the town turned out for the auction of our furniture and belongings stacked outside in the rain. It was December 6th 1954. I would be ten in three months. It was the last day we all lived together as a family.